From the blog of the Alphonsian Academy:

We asked some renowned moral theologians from different countries with ties of friendship to the Alphonsian Academy to write a post for our Blog. Our request to them was to write a comment on Fratelli tutti, nn. 256-262, by Pope Francis – these paragraphs discuss the very topical theme of the injustice of war. This is the fifth contribution of the series.

Pope Francis returns to a frequent theme of his: «War is the negation of all rights and a dramatic assault on the environment. […] We must work tirelessly to avoid war…» (FT, n. 256). It is not an original idea in papal teaching. However, Pope Francis concretises it with a particular assessment of current circumstances. He notes in paragraph 258 that «in recent decades, every single war has been ostensibly “justified”». He concludes that «it is very difficult nowadays to invoke the rational criteria elaborated in earlier centuries to speak of a “just war”». Does this imply a development of the just war theory, or is it an appeal to replace it with a moral principle?

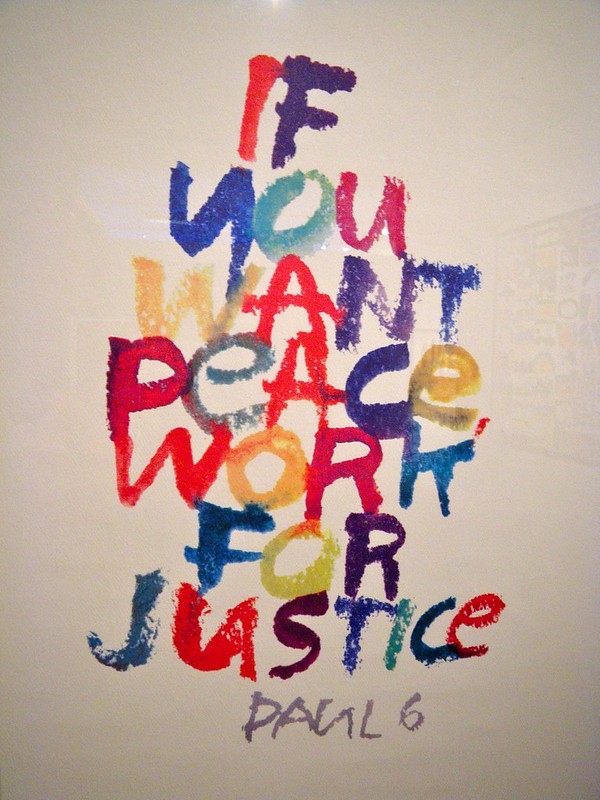

The four conditions of just war theory are repeated in The Catechism of the Catholic Church (n. 2307). It leaves evaluation for the moral legitimacy of war to the judgment of those responsible for the common good. If there has been a justification for every recent war from some side, the development of just war theory becomes problematic. Safeguarding peace is the framework in which the Catechism places the just war principle: «Peace is the tranquillity of order, since peace is the work of justice and the effect of charity» (n. 2304). Recent papal history of just war theory shows some development in its application. John 23rd repeats it, but notes it is not a suitable way to restore rights to people. Paul 6th linked peace with structural justice: the violent use of arms is not compatible with it. John Paul 2ndgoes further by rejecting that justice can be sought through a recourse to war. Benedict 16th has a typically incisive analysis of how love of enemies is the nucleus of the Christian revolution: it is impossible to interpret Jesus as violent.

Noticeable in this is how just war doctrine is retained but then placed in political contexts of succeeding decades. The approach of Pope Francis is a summons to reconsider the logic of just war doctrine itself. Peace seems a sort of loose end to the doctrine though the criteria are linked to the general aim of establishing peace. History shows the illusory nature of this aspiration: the ending of one war, however peaceful the intentions of those agreeing peace terms, plants the seeds of another war. The Versailles Treaty (1919) ended the Great War, but led to the “little” wars of our time Aristotle argues that establishing peace is the only legitimate aim of war, a point repeated by Augustine, attaining peace must be the central aim of war. The application of the just war doctrine is a cautionary tale for peace-lovers.

Some theologians are analysing the possibility of a just peace theory rather than a just war one. Stahm has written on Ius post bellum and just peace (2020), outlining different approaches: just war theory itself, peace-building practises, and transitional justice. Just peace as a replacement for just Ωar doctrine should be further considered. There are vigorous opponents of this idea. Latham has written provocatively on Just Peace Theory: A Syllabus of Errors (2020). In view of the reservations, particularly undermining Augustinian realism by Pelagian Utopianism, it is wiser to speak of a just peace-making. Peace is always a process. Blessed are the peacemakers. Among other advantages, this resonates with Optatam Totius, n. 16, to base moral theology more clearly on Scripture. A doctrine of just peace-making corresponds to this mandate.

Raphael Gallagher, CSsR

Professor emeritus of the Alphonsian Academy